Raised in a border town of the Cattauraugus Seneca Indian Reservation where his father was chaplain at the Indian school, Glenn Schiffman has lived around and with American Indians all of his life and counts many relatives among American Indians.

He has been interviewed by print and TV news organizations including CNN, and appeared in two TV docudramas regarding Native American lore. In addition, he served as the Go-Between on a documentary of a dance performed by Arapaho to celebrate the 1994 release of wolves into Yellowstone National Park. He is a co-founder of Roots and Wings, a non-profit organization which counsels youth and uninitiated adult men in collaboration with Native Elders and counselors at Home Boys Industries.

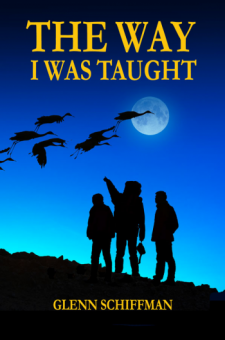

His highly acclaimed novel The Way I Was Taught is reviewed here.

GLENN SCHIFFMAN INTERVIEWED BY LEILANI SQUIRE

LEILANI SQUIRE: You were raised near an Indian Reservation in upstate New York, and your father was a minister for that Reservation. What an unusual and special childhood! How did those experiences influence your life? How have they informed your life as a writer?

GLENN SCHIFFMAN: Many everyday reservation experiences are mystical, ethereal, and by that I mean there was and is still a daily conversation among traditional people; a conversation about and between immovable and movable places wherein time is made real. Answers to difficult questions are often found in old stories. Identities are rarely individual, rather they are tribal, clan, and in modern times community. A relative or friend, never the individual, always describes any heroic action. Names change with the growth of an individual. Names given at birth rarely carry into adulthood or even past puberty. Among the healers and sages and seers, the goal was to lose one’s identity.

But in their modern context, there’s a poverty level on reservations that is unknown to most Americans. As a child I could deal with that because I didn’t have many material goods myself, and I never had the wherewithal to buy anything. As a child I also saw the hypocrisy of many Christians from what they preached to what they did. On the rez one becomes aware of the very physicality of life. Rez life is very depressing and dysfunctional. A functional family is abnormal. The influences from my childhood are re-measured every time I return to a reservation; and I return every year for weeks at a time. I see the everyday life and then I go to ceremonies where the old spiritual practices and ways give people pride and hope.

The old ways, the ethereal, affected my writing profoundly. The old ways taught me to see the world as a whole. I write from a very nonlinear mental circular outline. I bookend my stories and chapters. Many of my chapters can stand-alone and with revision could be short stories. I write slices of life that are metaphorical. As to the words “life as a writer,” I only began to write every day after having retired, and I write to leave a legacy for future generations. Often, my stories are about poor choices and their consequences, because traditional teachers follow that formula. One of my favorite expressions I learned from my elders is: “Experience is a tough teacher. First she gives you the test and then she gives you the lesson.” I was taught by being tested first.

LEILANI: The Way I Was Taught was inspired by your associations with the Reservation, and what you learned from the Elders. What was your process of writing a fictional character based on your life experiences? What was the biggest challenge to make the main character come alive?

GLENN: The way I was taught, there are no beginnings and endings. There is only open and close. Also, everything is a place. Once I have the title to the book, I have the context, but I don’t begin most chapters until I find the best opening sentence; the sentence that opens the door to the place the chapter occupies. For instance; The Way I Was Taught opens with the line, “Halfway through my eleventh walk around the sun, I was charged by a bull.” That sentence is more than a beginning; it opens to a space of experiences unfamiliar (walk around the sun?) and unusual (charged by a bull?) and yet believable. (In fact, I was chased by a bull as a child and it was terrifying.) As far as other chapters: I search through poetry for great one-liners. Chapter 3 begins “The liquor of hemlock bark and the manure of ducks and chickens fermented the air of my hometown of Bethlehem, NY.” I took the words “liquor of” and “fermented the air” from a Pablo Neruda poem. Again, the line opens to a space unusual but believable.

As a boy I learned to listen, not only with my ears but with all my senses. I also learned that intuition is a sense. I learned that everything has a language – all animals, plants, and the elements like water, fire, stones and air. Every time we take a deep breath the atmosphere is telling us something. But all those languages can’t be heard; they have to be seen or felt or tasted or smelled and often intuited.

Biologists now say that trees are social beings. They count, learn, remember, nurse sick members, warn of danger by sending electrical and chemical signals through a fungal network. I learned that as a boy sixty-five years ago and my intuition told me it was true. I learned that when someone goes hunting, that the game knows you are coming. I learned to pray for a deer to give away so that the people could live. But, guns spoiled all that, partly because hunting has become a sport. Most hunters do not eat what they kill. But I digress. How did learning to listen help me as a writer? I write even when I’m not “writing” all day long with my eyes, ears, all my senses. Mainly I watch and listen. The process requires ego-sacrifice, sensual-seeing, hunting to survive, and spiritually intuiting.

I would get guidance all the time. The elders would interpret my visions and dreams and teach me about what I was seeing so that I did not begin to think I was crazy, because in the Christian, dominant culture if I described what I saw people would say I was crazy. If a dream or vision was the portent of trouble, I was taught to “change the face of it.”

“Just talk to Spirit or the spirits as you would to anyone,” the elders said. “And be specific. Tell the spirits, ‘I don’t want something to look like this or happen this way – is there anyway you can change the face of this?”

Sometimes the answer was no. Sometimes the answer was yes, but with conditions. Always, I learned nothing is free, especially not in the spirit world. Or, I would be taken into a “burning water” lodge, a sweat lodge in Anglo terms, and be cleansed of some trouble or misfortune.

There’s a lot of heartache in The Way I Was Taught. People die, there’s disillusionment, and there’s cruelty. “Life is good but it isn’t easy,” Haksot would say. The biggest challenge was to communicate that knowledge with compassion and understanding.

LEILANI: What do you want people to learn from the story and the main character’s journey? Name the one thing most valuable that you learned from writing The Way I Was Taught that you will carry with you?

GLENN: I wrote the book primarily to juxtapose American Indian traditional ways and teachings with American Christians’ ways and teachings. The word “Way” in the title is a double entendre. The two worldviews I juxtapose are easy to encapsulate. The dominant-culture, Christian worldview is patriarchal and temporal and worships the Light. Earth People, traditional people who believe their souls are prayers of an Earth Mother are matriarchal and spatial and are aware that heat is the most transformative power in the Universe. In my book the Christian woman is weak, damaged and the father knows best. But in the rez world Grandma Minnie is strong, wise, tolerant, sensible and nurturing. The dichotomy sits on the page plain as day, and yet I believe readers get so caught up in the story and the plight of the archetypal orphan child that that symbolism is subliminal.

What I carry with me and practice to this day are experiences and ceremonies of the profound spirituality of the traditional people. I also carry with me gratitude for the privilege of having witnessed the miracles and felt the transcendence of faith in that spiritual knowledge. What I carry with me is humbling because I was and am still allowed to enter a world I did not and do not create.

In the world I and we all do not create – some call it a parallel dimension or a separate reality – there are spiritual languages, none of which are spoken, though one of them is songs or chants and one is rhythm and dance. All the ceremonies in which I have participated are conducted in a circle around Fire. (The Sun Dance is a prime example.) In every ceremony Fire shows me another form of the nature of duality: there are subjects (heat, coals) that experience and objects (light, flame) that are experienced, and the spiritual ‘other side’ exists between the two and is veiled from both by it’s language.

One spiritual language is color. In color perception, is the color a property of the object? Most researchers now agree that color is a property of the object as well as that of the brain, in other words, it is both object and subject. When two people look at the color yellow, they may agree they see yellow because that name has been assigned to what they are seeing from birth. And certainly, yellow is a color of the spectrum, but there is no way to prove that what I see and call yellow is what you are seeing and calling yellow. We take it on faith, which is why colors are a spiritual language.

In The Way I Was Taught I explore the point of view of the perceiver of color and link it to intention. In the novel I am currently working on, I consider the property of color and link it to randomness. When intention and randomness synchronize, transformation occurs. In a ceremony conducted by an Intercessor, i.e. “One Who Knows,” that transformation is intense and profound. It can cure cancer, ALS, diabetes. But, it is demanding and taxing to be an Intercessor because one must live and move in the profane and spiritual worlds. (They are not separate worlds; they are a continuum like the space/time continuum.) It requires great discipline to cross the veil into the spiritual to gather power and bring it back to bless the people and the land. One must enter through the door of a ceremony into a timeless or “Now” Place where there are points (the intercessor changes or shape shifts or becomes invisible ) and is picked up Power. Medicine people, the Intercessors, when they return become conduits (‘hollow bones” Fool’s Crow called it) of that Power.

LEILANI: You self-published The Way I Was Taught, which has won awards and has been listed #1 on Amazon. Tell us which awards you won and what category on Amazon. You must be proud of and happy with these accomplishments. Please share with us your secret of success. What would you do differently to be more successful?

GLENN: The secret of my success is my halfside, Barbara. She edited the book, figured out the formatting for Create Space, and along with the publisher of our coloring books promoted it to be #1 bestseller on Amazon in its genre: Native American fiction.

The Way I Was Taught was one of six winners in the general fiction category of the Eric Hoffer Awards. It was also a runner up for a Writer’s Digest self-published fiction award. On Amazon it is listed in Native American Indian fiction and for several weeks was outselling Sherman Alexie and Louise Erdrich. Because of that five distributors picked it up. I am still getting quarterly royalties from Amazon, though I haven’t done anything lately to promote it. To be more successful would take more promotion; probably a national publicist. My plan, though, is to gain recognition for my book about my life as a “roadie,” and then promote my other books. One thing I am doing – I culled one chapter from The Way I Was Taught that describes a near death experience, and I have sent that to several journals.

LEILANI: You have also written a novel about your days as a roadie for the Rock and Roll bands in the 70s. What did you enjoy most as you wrote? What was the hardest part? What are your plans for the novel?

GLENN: From 1971 to 1976 I spent over 1100 days on the road touring with over 40 of the highest grossing Rock’n’Roll acts of those times: Led Zeppelin, Chicago, Blood Sweat and Tears, Cat Stevens, Loggins/Messina, Beach Boys, Ike and Tina, Yes, Queen, Elton John, Dr. John, Elvis, The Eagles, Leon Russell, Blue Oyster Cult, Kiss, Springsteen and the Rolling Stones to name some. I worked for a concert sound provider and went from band to band like a piece of equipment. In 1975 I was on the road for 305 days.

I have written a novel, Life In The Fast Lane, based on true stories. It might be called “Creative Non-fiction.” Stylistically it’s a cross between Hunter Thompson and William Least Heat Moon. I fictionalized all crew members names. The rock stars play themselves. My life in rock and roll describes the backstage world as an underworld. What did I enjoy most? – The way I “played” with the plot and the main character’s arc.

Plots don’t interest me much. Plots are yearnings, which are challenged and thwarted, and they have hooks on which to hang characters and language. Don’t misunderstand, I do understand what a plot does. I know I must open the story at the point when my protagonist is on the brink of something good or bad, goal or choice. Obstacles are critical; they promote growth. In Life in the Fast Lane, most of my obstacles are other characters, primarily bosses such as managers, promoters, and vain-glorious rock stars. I know my reader should be rooting for my protagonists, even if he’s not really a likable guy. I know action has to be advanced.

I’m interested in educational strategies, not plots, and I’m interested in words that have rhythm, climb ladders, paint portfolios, and challenge thinking. And I love similes such as “alkene alley” (even if they seem out of place in a book about rock’n’roll.) Sentences that glide make me happy. I’m very visual so my descriptions are vivid, but I want them to be more than that. I want my scenes to vibrate.

(For instance: Annie Dillard once locked eyes with a weasel, and later on paper remembered (it was) “thin as a curve, a muscled ribbon, brown as fruitwood, soft-furred, alert.” In exploring nature’s mysteries, she is a master. That scene vibrates.)

The arc of Life in the Fast Lane follows Campbell’s hero’s journey arc, although it may not be readily apparent because the places and time line of the road stories is non-linear while the narration occurs on one day and in one town. The one day and place “literary conceit” is Joyce’s Ulysses and the road stories’ “literary conceit” is based on Aeneas’ search for a city in the Iliad. In both of my stories’ conceits there are guardians, challenges, helpers, mentors, abysses, death and rebirth, and atonement. At the end a gift of knowledge comes from a goddess in the town story, and a gift of redemption from a gay black man in the road story.

Life In The Fast Lane begins and ends with a snoring dog. Within the body of the story three dogs die and a fourth – the one snoring – is a rescue. All of them are threshold guardians at some point. The sacrificial three died that the narrator would survive.

Simply put, the death of a dog symbolizes suffering and pain in the life of the author, so depicting the killing of a dog, on a psychological level, represents a significant trial or pain a writer hopes to convey but finds too difficult to present on a personal level.

The hardest part was depicting the deaths those dogs and the killing off of some other “darlings.” One character, a working girl named Hope, who rode with me across Canada I turned into a device, a foil to whom the narrator told some of the most devastating and revealing stories of how seriously damaged and unfeeling and soulless my first person narrator had become. Hope became such a powerful character, though, that I had to get rid of her halfway through her time with the narrator. That wasn’t easy, because I liked her so much, but it created an epiphany moment for the narrator.

I am organizing and producing a “staged reading” and DVD recording of parts of the book using professional actors and even some rock stars to read passages. A larger project is to create staged readings of stories from production crews – crazy incidences – but with an arc and point of view like Life In The Fast Lane has.

LEILANI: Recently, you published two coloring books that are part of a series. Why a coloring book? What is the series about?

GLENN: The stories are educational stories from American Indian Lore, different tribes, and they are for people ages 8-80. There are five books in the series and we’ve so far published one for all the seasons, one for spring, and one for summer. The autumn book has just been sent to the graphic artist.

I read a lot of American Indian “How to Live” stories – stories from the deep past that educate rather than entertain. Often, I am able to make them relevant to the modern world. The Seneca version of “Once upon a time” is “This really happened, even if it didn’t.” Among the Iroquois the “trickster” is a Raven. Trickster stories are almost always about “how not to live.” They aren’t true, but they feel true.

Coloring is meditative. Coloring parties are springing up all around the town. We arranged American Indian fables and trickster stories with black and white pictures. The pictures and stories relate. The stories are moral lessons, how “not to live” lessons, and sometimes warnings. They are family friendly. For the name of the “Unnamable” I have used Great Mystery throughout. The first book was 90 pages. For $10 it’s a wonderful gift.

LEILANI: Putting a coloring book requires collaboration with others, such as an artist or illustrator, an editor and publisher. Has the process of collaboration helped you become a better writer? If so, how? If not, why?

GLENN: For the past fifteen years I have been telling one story pertinent to each season at a medicine wheel ceremony that meets each equinox and solstice at an ecological resource center in Malibu. I’ve collected a lot of stories. That collection was/is the impetus for creating the coloring books.

I present an introduction to the season in each book that has the tone and syntax of the stories within, but is all original from me. I also edit the stories and sometimes explain the language or an event that is mystifying to Westerners in order to suspend disbelief and bring modern world relevancy to them. So, yes, putting these oral stories on paper and making them relevant has “made” me a better writer, but the collaboration part is between my editor and publisher. Once I turn it over to them, it’s out of my hands.

The Greek philosopher Apollonius said of Aesop, “He made use of humble incidents to teach great truths, and after serving up a story he added to it the advice to choose to do a thing or not to do it.” I follow that lead also, although “added … advice” is not in most American Indian fables.

LEILANI: You have been prolific the past few years, writing one novel after another. What drives you to write so consistently over a long period of time? What is most challenging for you to sustain a writing life?

GLENN: I have three goals in writing dramatic fiction. Two sustain me. One is to tell the truth. The other is to lie. On the one hand the entire enterprise is a lie, a fiction, something that doesn’t exist but is made to represent something that does. On the other hand it is all a pursuit of truth, of what is real and resonant and relatable. Otherwise I am not communicating an understanding of what my words, my stories have to do with all of us.

The Way I Was Taught is not a memoir, not a true story, but it is based on a world I know very well. It’s believable, like a good lie. I quote an Anishnabe saying: “You’ll never understand the truth until you understand the beauty of a lie.”

In my current novel, The Long Dark: A Personal Chant, my protagonist visits the Battlefield at Gettysburg, goes back in time, and relives the fight for Little Round Top. It’s an extraordinary and fantastic scene, but believable because of the threads of mysticism and the previous visions of the main character. The fact that it really happened is irrelevant. Remember the Seneca opening, “This really happened, even if it didn’t”? Managing the viewer’s ability to believe is part of the writer’s job.

My third goal I’ll explain in the answer to the next question.

LEILANI: You belong to a writers group and have for a few years. How has this helped you as a writer? What do you feel is the most productive aspect of belonging to a writers group? Anything to be wary of?

GLENN: I follow an inner voice when creating a very personal work. But somewhere, usually the writer’s group, I will come up against the fact that I have to do more than follow an inner voice. I have to have craft. My “unique” voice will be challenged and I will be faced with a choice—do it my way or eat my ego. I have learned that if the majority of the group “don’t get” what I’m doing, it’s not their fault.

But then, when I start re-writing and start imposing a worldview that I think will communicate my point to the group more successfully, I encounter a difficulty of a different kind. My characters want to go somewhere I don’t intend. They may be proving a point (e.g. that people are good) even when the whole point of my story was supposed to show people are despicable. Re-writing is adjustment after adjustment. It’s more ego eating, more killing off darlings, and often means starting over – finding a new opening. Readjusting time by expanding or contracting space.

I have learned during five committed years with the group to write the first draft in third person, and get distance from the story, plot, strategy, main character. With distance and understanding I rewrite in first person. It always is better (in my mind) but it does require serious changes, since in first person the protagonist cannot know what an omniscient narrator knows. In first person the omniscient’s knowledge is revealed slowly – lessons are learned only after the test has been given. Also voice and style change somewhat.

One difficulty I encounter with my writing group is that I see time within a place, as opposed to plot with a time arc. (This viewpoint is difficult to explain, but “Halfway into my eleventh walk around the sun” paints a different concept of time than does “when I was 10½ years old …”) Regarding time, the grandfather character explains: “In so many Earth People languages, the only word for time is ‘now.’ In my language the word for time and the word for forest are the same word and it also means ‘now.’ Think about that. Time is a forest and it’s right-now. There are no beginnings and no endings in a forest. It’s a constant circle of life and death. If I plant this seed and it sprouts, is that a beginning? No, it’s a ‘to be continued.’ Everything is a different age, and it’s all connected. That’s how I see it.”

That makes total sense to me. Subsequently, I tell stories that exist long before I open a door to them and long after I close the door on them.

I am cerebral so my narrators are often cynical and ironic from the opening line, because even though they are aware of the invisible and impenetrable barrier that stand between the mind of man and the Mind of God; they still do everything they can to find and cross that barrier. Lao Tse is quoted: “A human is sane if he or she does not try to measure the immeasurable and name the unnamable.” My characters don’t listen to that until they learn it from experience after experience. My characters measure and name even though their author knows it is insane to try. Some, perhaps many of my characters are not likeable, and writers in my group have told me so. Also, I like to quote psychologists and poets and philosophers and literary figures within dialog, and some find that off-putting or distancing. Most of the critiques of my writing are about the characters lack of feelings, or perhaps the observational way I tell the story, even though it is first person. When I get that critique, I simply work that point about the character into the next chapter, or the re-write of that chapter in some way.

Another thing: In my novels I write about a time period when white men in particular were misogynistic, homophobic, and ethnically racist. I use the vernacular of the day in my dialogs, and it gets pretty heated. Many in my group who are next generation are very put-off by my language. I sense there is judgment of me that may cloud their critique of my story. I am inclined in rewrite to be politically correct by today’s standards, and have to resist that, but it’s difficult because I also want not to be judged.

As to “wary”? Interiority, the quality of being interior or inward, and alterity, the state of being other or different, are goals I explore in my current novel. Otherness, or alterity, is a function of the making of identity, because that which is other is not outside of identity. Alterity implies that one’s definition of an outsider affects ones interior social order. In psychology alterity or otherness helps us understand projections. That which I recognize as you is “in me.” When I ask, “’Who are you?’ I am asking, ‘Who am I?’”

So, if I am wary of anyone one in the group, it is because there may be people in the group who are wary of me due to my overt lack of political correctness. I don’t know, though, because I may be recognizing wariness as judgment.

LEILANI: What writing project are you working on now?

GLENN: The Long Dark: A Personal Chant. The novel opens with: “I changed my name from Hunt to Clay on the train ride from Buffalo to Philadelphia. Nothing is permanent, right? I figured if I had to ‘learn to dance on the straight line’ as the medicine man Big Kettle had said when I was banished from learning the old ways, I would do it using the name ‘Clay,’ first because of the symbolism. Second, it gave me a kind of divorce and distance from my old life. But mostly the change was about identity.”

The Long Dark: A Personal Chant is a novel that explores a boy’s life from the time he is a 12 year old forced by court order to leave the custody of his father and live with his mother and grandfather. It opens in 1954 and closes at the rock concert at Altamont in December 1969. During those fifteen years he struggles with the notion that he is cursed, and in fact someone dies or a tragic event occurs in his immediate proximity in each chapter. In one chapter he visits the grave of a Civil War soldier he believes was his in a former life. In that chapter he attempts to come to grips with the source of his curse – “the Black Wand” – which he feels makes him an Angel of Death. He remembers a story he was told about “Gha-Oh, Impermanence” which helps him survive his torment, but pitches him into several years of aimless, nihilistic, pleasure-seeking living culminating in his entering the underworld of rock’n’roll, the third book in the series.

He also learns during those fifteen years to “dance on the straight line” as he was admonished to do in The Way I Was Taught, the first book in the series.

The fourth book in the series, (I’m a Hermann Hesse fan as well,) is titled Moves Standing Still. It’s the journey of the narrator’s return to the spiritual world of the American Indian. I haven’t begun to rewrite that one yet.

LEILANI: Do you think writers need to read?

GLENN: My mother taught me to read simple sentences by the time I was three. And from then on I was required to read a book a week, any book but it had to be challenging, until about the 7th grade. When I started getting homework, my mother stopped giving me hers. I read Huckleberry Finn at least twice when I was eight. That book had a profound influence on me. I also read Richard Halliburton’s Complete Book of Marvels before I was 10. I loved that book. In 2nd grade I was reading at a 6th grade level. My mother lived to be 96, and near the end when I would visit she would always ask, “What book are you reading?” Mom, wherever you are, this week I am reading To Show and To Tell, The Art of the Personal Essay by Philip Lopate.

Here’s some scientific evidence of the value of reading fiction. Science says it’ll make us better at interacting with people. Poetry stimulates parts of the brain linked to memory and sparks self-reflection. Reading enhances connectivity in the brain, but readers of fiction? They are a special breed. A 2013 Emory University study looked at the brains of fiction readers. Researchers found heightened connectivity in the left temporal cortex, part of the brain typically associated with understanding language. The researchers also found increased connectivity in the central sulcus of the brain, the primary sensory region, which helps the brain visualize movement. Fiction readers tend to be more aware of others’ emotions. In the study, empathy was only apparent in the groups of people who read fiction, because “the same psychological processes are used to navigate fiction and real relationships.” Fiction is not just a simulator of a social experience; it is a social experience.

“Before writers are writers they are readers, living in books, through books, in the lives of others that are also the heads of others, in that act that is so intimate and yet so alone.” (Rebecca Solnit)

“At the hour when our imagination and our ability to associate are at their height,” Hermann Hesse asserted, “we really no longer read what is printed on the paper but swim in a stream of impulses and inspirations that reach us from what we are reading.”

LEILANI: What books do you like to read? Publications? Journals? Who is your favorite author?

GLENN: I read the LA Times thoroughly every morning. I read five weekly magazines, also ten journals that come monthly. All are journals that I think will accept my stories and/or poems. American Indian writers past and present heavily influence me. Favorite writer? Impossible to say. Four that have influenced my voice – Mark Twain, Franz Kafka, Annie Dillard, and Carlos Castaneda.

LEILANI: What advice would you like to pass on to writers? Or anyone?

GLENN:

Fiction is an art form that requires time. Be patient. Write, Rewrite, don’t quit. There’s a lot of mechanical work to writing. There is, and you can’t get out of it. Hemingway wrote A Farewell to Arms at least fifty times, according to him.

Learn to ask for Invisible Help. This means cultivate a friendship with the unknown. I overhear my own voice speaking out of the unknown and into the world. To get there I ask for help from elemental powers and archetypal guardians I’ve encountered on my road.

Every day I write an analysis about what I see in the world. Or want to see. Or want to teach. I do this in a public way on Facebook or my blog. Or I tell or show with words how to do something. This really is useful, even though my focus is fiction. I should write fiction every day, but I don’t. With my fiction the “public” aspect of my writing is going to my writer’s workshop and hearing critiques.

Never compete with living writers. Compete with the dead ones you know are good. If you have a story like someone alive has written (and this is mostly pertinent to screenwriters), write a better one. In any art you’re allowed to steal anything if you can make it better, but don’t ever imitate anybody. All style is, is simply the way a writer states a fact or paints a lie. If you have a style of your own, you are fortunate, but if you try to write with somebody else’s style, your facts will be lies and your lies facts.

There’s a gospel song called, “Hallelujah Anyway.” Everything’s a mess, I’m going down the tubes financially, and gaining weight … Well, “Hallelujah Anyway.” And keep writing.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Leilani Squire has facilitated creative writing workshops for veterans and their families throughout Southern California and is a CCA Certified Creativity Coach. Her poetry and short stories have appeared in various periodicals. She has completed her first novel, Fancy House about sex trafficking, and is beginning her second.

First published: http://bookscover2cover.com/ |