|

Comment on this

article

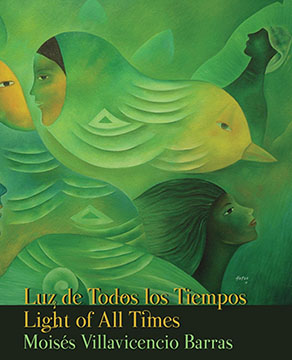

Luz de Todos los Tiempos/Light of All Times

by Moises Villavicencio Barras

29 poems/ 87 pp/ $15.00

Cowfeathers Press

cowfeatherspress.org

Reviewed by: Ed Bennett

No matter what our politicians may say about us, we are a nation of immigrants. For many of us,

the story of an ancestor's journey here has become fogged with the passage of time. For a few

of us, we have seen personally the effect of that journey on a close relative. My own grandfather

came to the United States barely out of his teens, joined the army, worked every day of his life

and never failed to praise the opportunity he found here. There was always a longing, an almost

mystical longing about the "old country", a phrase that I have heard from immigrants from several

continents. Admittedly, the longing revolved around memories of family and of growing up and

occasionally about the poverty. While America was their dream, that dream arose from the culture

that taught them to dare to achieve it.

With the current dialog on immigration abrading the political landscape, Moises Barras' book, Light of

All Times, presents a more nuanced, almost mystical, impression of our country through the eyes of someone

who has embraced a new culture while being true to his past. The importance of this book, aside from the

excellent poetry, is the assertion that the people who choose to settle here are indeed Americans yet their

memories of their past transcend categories, giving a depth to their appreciation of the American dream. Mr.

Barras, a native of Mexico, has written 29 superlative poems in both Spanish and English, juxtaposing them

as if placing a mirror between them. Difference becomes sameness, languages reflect the same thought and the

book becomes a description of one poet's journey to a land both rich in possibility yet occasionally hostile.

The first poem in the book, "Ancestros"/"Ancestors" examines the idea of sameness and difference as it applies

to his own family:

"My ancestors sang

In the prairies where infinity lives…

My ancestors walked from one side

To the other side of the earth quietly

With their mouths in the ruinous waters

That rain leaves

After dying in leaves and stones…

I am one who still walks the prairies

inventing myself

speaking the language of things."

These words capture the "mystical loneliness" mentioned above yet it highlights the differences with his ances-

tors. Yes, despite living in urbanized Madison, WI, his heart is still in the prairie but he no longer speaks a

language of the quiet acceptance, he speaks of "things". There is no judgment of which of these is better, they

simply are. The interesting effect of having both English and Spanish shows how, in some instances, English does

speak of "things" while the Spanish more accurately paints the scene. The lines …the ruinous waters/that rain

leaves/after dying in leaves and stones" is somewhat cumbersome because of the identical spelling yet different

meaning of "leaves". The original Spanish:

"las aguas ruinosas

que la iluvia deja

despues de morir en las hojas y las piedras."

The poet speaks the language of "things" as he invents himself yet his native Spanish creates the exact image he

wishes to convey.

The dichotomy between old and new countries is a theme woven throughout this book. His poem "Tia Estella's Feet"

tells us "Tia Estella's feet /never knew shoes. /They were flesh of the road". In "Madison" he states "We find

life and things/like the small rainbow of car oil on the sidewalk". In the streets of Wisconsin, again, he speaks

of things but with his Aunt Estella, she is part of the world, part of existence that is beyond the simple name

of an object. The English/Spanish translation is telling: he does not translate "Tia Estella" into "Aunt Estella'.

He maintains her title in both languages, as with a child of immigrants who use the appellation as an endearment

as well as a name.

My biggest problem with this critique is actually culling out poems to highlight when every one of them is so well

written that they deserve mention. The fluid voice of Mr. Barras throughout leads us from one poem to another with

the slow pace of two friends walking together as they speak of the profound as well as the mundane. Even if one does

not speak Spanish (for the record, I do not) the presentation in both languages enhances the beauty of this book

rather than distracts.

Moises Villavicencio Barras has written a timely book that has appeared when the topic of immigration finally has been

recognized by both political parties. But that is simply the "thing" of this book. Luz de Todos los Tiempos/Light of

All Times is a bridge beyond ignorance, an important step toward acceptance of everyone. More importantly, it is the

eloquent reply of a talented poet to Emma Lazarus' "The New Colossus" carved on our most famous icon in New York Harbor.

Return to:

|